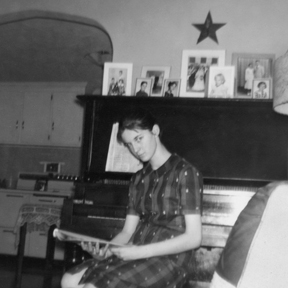

Makeupby Darlene Frank When school opened in September of ninth grade at Pennridge High, everyone looked fresher and older and bigger than they had three months earlier when school let out. Like they’d been oxygenated and enhanced in some mysterious way over the summer. I wasn’t prepared for the transformation. Boys in crisp crew cuts and new glasses, jostling and boisterous against the backdrop of lockers snapping open and shut. The girls dazzled: Rita Landis’s dark hair draped liquid smooth on her shoulders like the Breck shampoo girl. Pam Fretz boasted a blonde pompom of curls, petite tweezed brows, and pink lipstick. Debbie Detweiler was a bombshell. Red lips, sleek pageboys, and perky bangs were everywhere. The girls’ faces were paintings, flowers, works of art. And I—long hair in a bun, half my wardrobe made up of ill-fitting hand-me-downs from Aunt Rhoda, no decoration on my face—I felt washed out and unfinished. A plain Mennonite girl. And frightened to look so unlike them. I had no close friends from eighth grade at this school. Besides, we’d been shuffled into different sections this year. New homeroom, new classes, with kids I didn’t know. Who would want me as a friend? I couldn’t beg my mother for permission to wear makeup, as I had begged (without success) for short hair, since no Mennonite woman had yet set a precedent. Wearing lipstick was as unthinkable among the church women then as was drinking or dancing—no one had started doing it yet. So I set my own precedent. In the five-and-dime, I wandered off from my mother to the makeup aisle and surveyed the assortment of goods that other women used without prohibition. Spotting what I liked, I slipped it into my coat pocket. It was easy to steal back then, no security cameras or people walking the aisles scouting for shoplifters. When no one was looking, I took what I wanted, perhaps with slight worry I might get caught, but desire winning over fear every time.

I began, ever so gradually, to trim what might pass for a few bangs on my forehead. “You’re not cutting your hair, are you?” Mom asked. “Of course not,” I said. “They’re wisps that keep falling forward.” Halfway through my junior year Mom relented on cutting my hair. I had to promise I’d let it grow back when I was older, whatever that meant, whereupon she chopped it to shoulder length. Freed of the bun and hairnet, and with my secret beauty cache, I felt almost normal. The day after the haircut, a football player seated behind me in journalism class lifted the hair off my neck and let it fall back. “I like it,” he said. To say I felt pleased is an understatement. One school-day morning the following year, I went to the breakfast table as usual. I normally spent less than ten minutes there. It was a daily lookout post for my parents to inspect my hairstyle, and I was always relieved when the time passed without comment. This morning Dad was eating his cornflakes, the radio was tuned to the news and the weather report, and Mom stood at the table wrapping sandwiches in waxed paper for his lunch. I drank my orange juice from the blue plastic cup with the silver sparkles on it and poured Wheat Honeys into my bowl. I took a taste on my finger from the thick lip of cream at the top of the milk bottle, and added milk to my cereal. “What’s that on your face?” I tensed at Mom’s sudden words. “Around your eyes.” She was looking at me, appalled. Dad looked up from his bowl. “What?” I asked. I didn’t know what she was talking about. “Look at it! Go look in the mirror!” she said. “Look at her, Dad!” I went to the round mirror on the wall beside the refrigerator. “Home Sweet Home” curled in blue and yellow script at the mirror’s edge. I couldn’t believe it—there were black smudges under my eyes. I had forgotten to clean off the mascara from the day before. In my sleepy and nearsighted state I had not looked closely in the bathroom mirror before coming down to breakfast. I had stopped wearing glasses the day Shelley Reeve told me in the cafeteria line that my green eyes were beautiful and she had never noticed them because they were hidden behind my glasses. I couldn’t see everything but it didn’t matter. “I don’t know what it is,” I said. “It must be dirt.” Mom glared. “What kind of dirt? That doesn’t look like dirt. That looks like you’re putting stuff on your eyes.” “No, I’m not. It’s probably dirt, from last night. We were playing outside and I forgot to wash it off. Or maybe it’s sleepy dirt, from rubbing my eyes.” “You can’t fool me. It looks like you’re wearing makeup. Is that what you’re doing? Wearing makeup?” She was hostile. “It’s not makeup. I don’t know what it is.” I dipped into my cereal. The Wheat Honeys got soggy if you let them sit in the milk too long. “It has to be dirt.” “That doesn’t look like dirt,” Dad echoed. “What is your daughter up to?” Mom asked him. “She gets these ideas in her head that she can do whatever she wants, behind our backs. Thinks we’re too dumb to notice. “What are you doing behind our backs?” she asked. “Nothing,” I said. I knew I was in trouble and didn’t know how to get out of it. Usually I planned my lies and figured well in advance how I’d explain to cover my tracks. So far I’d been successful. But this had caught me off guard. “The Devil is really working on her,” I heard Mom say as I headed upstairs to brush my teeth and clean my face. Surely my parents talked after I left the house—about my waywardness, their growing concern over my rebellion, how they couldn’t afford to send me to the Mennonite high school, where this would never have happened. When I came home from school that afternoon I changed my clothes and went down to the kitchen, ready for Mom to drive me to my after-school job. She was usually waiting by the door with car keys in hand. Today she stood next to the kitchen table, between it and the door. Her keys lay on the table. Next to the keys were the lipsticks and eye makeup I kept in my dresser drawer, the ones I hadn’t carried in my purse that day. It hadn’t occurred to me that she might go through my dresser. She stood facing me, her feet planted squarely. “I looked in your bureau drawers today and found these,” she said. “I’m not driving you to work until you tell me what you were doing with this. I want to know where you got it.” I stood next to the table. I was determined to postpone, if not avoid, punishment. “I didn’t use it. It’s not mine,” I said. “Tell me the truth. Judy Derstine told her mother that ‘Darlene gets on the bus every morning wearing lipstick.’ I called Marion today when I found this. She thought I allowed you to wear it!” Mom sounded shocked that Marion could think such a thing. Marion was our loud and opinionated Mennonite neighbor. Her daughter, Judy, was younger than me. We weren’t friends; she had a brusque manner that I disliked. “Judy doesn’t know what lipstick looks like,” I said. “I’m not a dummy,” Mom said. “Do you wear lipstick to school? That was makeup on your face this morning! I think you’re wearing makeup at school!” “No, I’m not. It wasn’t makeup.” I was quiet. I could see we weren’t going anywhere, but this was a battle I was not yet willing to lose. I wondered what I would tell Mrs. Corwin about being late to work. She and all the staff at the boarding school where I served dinner to the residents each night knew I ignored my parents’ restrictions and lied to protect myself. It didn’t seem to bother them. I knew I would stop lying when I could move away from home and do as I pleased. “I don’t believe you,” Mom said. “I am not taking you to your job until you tell me the truth. I’m your mother. I don’t want you to deceive me. Please. I won’t even get mad if you will just tell me the truth.” Her lips were pressed in a firm line, the corners down, her eyes dark and determined. She looked nervous. Could I believe she wouldn’t get mad? She got mad even when we got sick, though I knew it was because she was more scared than angry. She spoke again. “All I want is the truth. I promise I won’t get mad if you just tell me the truth.” She sounded pleading now, like she wasn’t angry, just tired of arguing. She still hadn’t touched the car keys. I decided to face the consequences. Maybe she wouldn’t get mad. “Somebody gave it to me. I wore it a couple of times.” “Who gave it to you?” “One of the girls in my class.” I spoke cautiously. “She had some she didn’t need.” Mom picked up the car keys and put them in her pocket. She picked up the makeup and walked it to the wastebasket. “I’m throwing these away and I don’t ever want to find anything like this in your bedroom again.” In the car she got mad. She was too hot to hold it in, and pressing the accelerator seemed to release it. She lectured me on the evils of lying and disobeying your parents. This was serious business and I had better straighten out. When I came home from work that evening my parents announced the punishment: I would sit in the living room and read aloud to them from the Bible. This would teach me the error of my ways. I went to my room and got my Bible. I sat on the piano bench, facing them. Mom sat in the rocking chair next to me, Dad across the room on the sofa. He wasn’t reading the newspaper as usual, but waiting for me to begin. Every night at the supper table he read the Bible aloud before we gave thanks for our food and ate. He did this, I believed, not because it meant something to him, but out of habit because his father had done it. During the readings I fidgeted and played with my silverware to show my disinterest. Sometimes he would test me to see if I’d paid attention. “What’s the last word I read?” he’d ask, closing the Bible and glaring at me. This was not a hard test, and I always passed. I asked them now, “What am I supposed to read?” “Whatever you want,” Mom said. She sounded weary. I wanted to read a list of begats from the Old Testament. Adam begat a son Seth … and Seth begat Enos …. But I was no dummy, either. “Something from the New Testament. About how wrong it is to sin,” she said. I opened the Bible. It was bound in thin, smooth, black leather, my name in gold letters on the cover. I’d earned it by memorizing verses in Sunday school class. The memorization was required. I turned its tissue-thin pages slowly, deliberately, not looking at my parents. I chose an innocuous passage that would not invite further discussion. Maybe it began “And it came to pass that when Jesus had finished,” or “The light shineth in darkness.” I only remember that I read a few verses, not rushing through them, the words flat but enunciated, all the while plotting how to continue my ways and to do so without error. __________________ |

I soon accumulated a cache of beauty tools—lipsticks in bright pink and white and a deep purple-berry color, brown eyebrow pencil, a black mascara paint cake in a thin red box. Often, I opened the dresser drawer where I hid them just to admire the collection. To feel the weight of the heavy gold lipstick case in my fingers and twist it so the bolt of color slid up like a candle. To mark soft brown strokes on my hand with the pencil, hold the rich purple lipstick next to the white. The dry musky rectangle of mascara, the minute bristles of the brush that came with it, the faint perfume of the waxy lipsticks—all of it gave me a thrill. Every day at the school bus stop and in the girls’ bathroom I filled in my lips, drew lines in my brows, and darkened my lashes. I felt smug and bold and defiant. Less Mennonite. I rubbed off the lipstick before I got home. The eye makeup I left on because it didn’t look obvious and was not so easily removed.

I soon accumulated a cache of beauty tools—lipsticks in bright pink and white and a deep purple-berry color, brown eyebrow pencil, a black mascara paint cake in a thin red box. Often, I opened the dresser drawer where I hid them just to admire the collection. To feel the weight of the heavy gold lipstick case in my fingers and twist it so the bolt of color slid up like a candle. To mark soft brown strokes on my hand with the pencil, hold the rich purple lipstick next to the white. The dry musky rectangle of mascara, the minute bristles of the brush that came with it, the faint perfume of the waxy lipsticks—all of it gave me a thrill. Every day at the school bus stop and in the girls’ bathroom I filled in my lips, drew lines in my brows, and darkened my lashes. I felt smug and bold and defiant. Less Mennonite. I rubbed off the lipstick before I got home. The eye makeup I left on because it didn’t look obvious and was not so easily removed.